The Bird Sisters Transcript: a conversation with author Rebecca Rasmussen

An Art is Dialogue talk on running, mothering, and Wisconsin with author Rebecca Rasmussen of The Bird Sisters. Listen to our conversation here or here.

An Art is Dialogue talk on running, mothering, and Wisconsin with author Rebecca Rasmussen of The Bird Sisters. Listen to our conversation here or here.

| Rose Deniz: This is Rose Deniz for Art is Dialogue. Today I am talking to Rebecca Rasmussen about her book forthcoming this April (2011) called, “The Bird Sisters“.

I’m very excited to be here, talking to her today. Thank you so much for talking to me, Rebecca. Rebecca Rasmussen: Thank you for having me, Rose. It’s wonderful to be here, as well. Rose Deniz: Well, it’s really been a pleasure to get to know you online, actually. In fact, I think we met through She Writes, and then connected on Twitter and Facebook. I really enjoyed reading your blog and getting to know a little bit of the background behind your book, but I’d love for you to talk briefly about what we can expect from “The Bird Sisters” this spring? |

||

| 1:01 | Rebecca Rasmussen: “The Bird Sisters”… this spring, I guess that’s a big question!

Rose Deniz: Is it a big question? I’m sorry. [Laughter] Rebecca Rasmussen: Oh, no, no, no. It’s a good question. I’m just getting used to trying to figure out the best way to talk about the book actually, because for me it’s about so many things and so, trying to find a succinct way to kind of sum up what to expect is always an interesting challenge for me. But one of the things I think is that it really centers around these two women, Milly and Twiss, and their life in a very small town in Wisconsin called Spring Green. That’s also where I grew up as a kid with my Dad on our farm. It’s about their life together and how they’ve arrived at being old and alone in a house that they grew up in, but they’re not necessarily unhappy, though. They have wonderful happiness with each other in some ways, but then also great disappointments and others. |

|

| 2:08 | Half the novel is in the present tense, just going through a regular day in their life. They’re old, they’re not doing a lot of work, and it’s basically how they arrived in the present moment to be called “The Bird Sisters”, not necessarily a negative way in the town but in a, “yeah, the weird old bird sisters”.

When I grew up, I split time between my mom and my dad. My mom lived in Illinois and my dad lived in Wisconsin and in our town in Illinois whenever a bird would fly into a window, which happened often because it was the suburbs and everybody had those huge sliding glass, sort of 70s-styled doors all over the place. So it’s something that happened a lot. So my mom used to take the birds, put them in little cardboard boxes, and cover them with a blanket, and we’d take it to the bird lady. |

|

| 3:04 | So when I got older I started to wonder, “Who is it? Who is the bird lady? Why did I not know anything else about her, but she was a bird lady.” And we’ve always taken birds there. So that was one element of it. That’s something the sisters are sort of known as in the novel. And a little bit benignly, but with a little bit of a pinch there, they don’t have anyone else but themselves.

And then it goes kind of in the past, into the (19)40’s when they were growing up and some things that happened when they were young girls that they never quite got over, as a lot of us have in ourselves that things that kind of spoiled us in some ways. They’ve chosen to move on in some ways, but then they’re always drawn back to these moments of their youth. So, it’s about memories and about sisters, and about birds. |

|

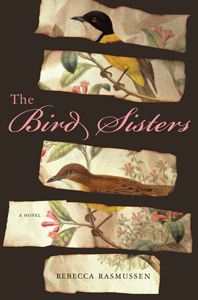

| 3:59 | It is pretty funny because people ask me all the time, “You must be a great lover of birds. Are you obsessed with birds?” You know, (birds are) on the cover, they’re bird ladies, and I do love birds. but I felt embarrassed that on my cover, there are two birds facing each other. For a while, I didn’t what kind of birds they were and I was embarrassed to ask my publisher because they’re like, “You’re the bird lady.”

So, I was doing all of this research and finally, I broke down and asked. They’re like, “I have no idea. Let me talk to the designer.” They’re called, “Ramsay birds”, Ramsay birds. It’s a sketch of an old Gould sketch, and he was an ornithologist from the 19th century. So, it was just pretty interesting that I didn’t know the birds and everybody expects me to like, “What kind of bird is that, Rebecca?” on the street, I’m like, “I’m not sure.” |

|

| 5:11 | Rose Deniz: …so now you’ve turned into the bird lady, too.

Rebecca Rasmussen: I am the bird lady. Like people say, “Oh, that poor bird,” and I think, “It is a poor bird but I don’t know how to fix it. That’s fiction, baby.” You know? Rose Deniz: That’s where I think that kind of magic happens when fiction can turn into the threads of your life too. If you’ve experienced something really deeply when you’re reading, you start to think that the things can turn out true for your real life. I had this question come to mind when you first started talking, because I nailed you with one big question. Your response was, “I’m trying to find a way to describe [The Bird Sisters] in a succinct way.” |

|

| 6:03 | My question was, maybe there are multiple ways to describe it and there isn’t just one specific pitch or a summary —. That maybe pinning something down isn’t always the most important thing to do.

Maybe it’s about finding that one little connection, whether it’s a bird lover, it could be someone who knows nothing about Wisconsin but yet, they’re really drawn to the sounds of how you described the earth and the people. Do you feel like you have different ways to describe the book in different places? |

|

| 7:01 | Rebecca Rasmussen: I feel it depends on my audience.

I’ll be very honest with you that I think that I probably did a more natural job of talking about my work before I had to deal with the publicity-side of things, Because when you sign with a publisher, one of the things that obviously comes up along the way is that blurb on the back of the book. — I don’t fault them for this at all, in getting what is the angle that they think will make people the most interested in the book. So, for many months I was working right alongside them – paring it back, paring it back, paring it back. |

|

| 7:57 | At this point now, even though it started off naturally, feeling like I would want to sprawl all over the place and answer questions in a more natural way, now I find myself just having to kind of let go in order to promote a book, versus what I really feel the book is about; what I think it encompasses.

So it’s different that when I first started, definitely. Rose Deniz: I think it will probably take shape over time, too, having to take a step back and look at it in a more succinct way. When you’re in the middle of writing as I imagine, you’re not thinking about the back copy so much. I mean, you might be because you might be imagining what it would look like, but you come to develop the language you need at the time that you need it. So now maybe you’re in a place that yes, you can kind of describe it differently than you would have in the beginning. |

|

| 9:16 | As you come closer to [your book] launch and then as you start doing book tours, how do you hope to integrate [public and private]? You’re going to be in a more public sense.

It’s kind of like being in two worlds, too. Rebecca Rasmussen: Yes, that’s definitely being in two worlds. |

|

| 9:52 | I think that most writers would say that they’re more comfortable doing the writing, being alone with the writing.

I am no different than that. I actually [wish I was] doing that right now, because right now it’s getting a little bit too busy to juggle making dinner, getting my daughter off to school, getting to sleep, functioning on a daily level and then also doing the things that I need to do that my publisher is asking me to do; you know, writing blogs versus writing my novels. So, I miss it. I really miss it. It does merge, too, and talking about it is wonderful, but this is truly never as wonderful for me as when I sit down to do the writing itself, alone. I actually just asked the publisher – I don’t even have a copy of the book anymore – I asked the publisher to send me one because I kind of want to experience it again, as much as it’s possible for me to do because I’m the author. |

|

| 11:01 | But as a reader, before I go out on the road and I talk to people, I just want to remember the little place I was in when I was writing it and what it means to me on a level beyond language. I want to get back that feeling of it. Like, “Oh my goodness that was a heartbreaking day because Milly did this,” and I can’t believe it but there are tears… and I’m not crying because I think, “Oh, blissfully good writing.” I’m crying because I’m sad about what happened to the character.

So, I am trying to get back to that feeling because I think that’s what people connect with anyway, but it is challenging when you have to do all these other stuff that, sort of, is related. |

|

| 11:59 | Rose Deniz: Well, it can take on the life of its own. That’s substantially what happens after we create a body of work and put it out there in the world; it does take on its own shape and its own form.

But maybe more so with being a novelist than, let’s say, a painter. A painter doesn’t necessarily travel with their work everywhere. Maybe they get to an opening and they talk about it, or they’re invited to talk, but inmost cases, the painter wouldn’t necessarily be there having to speak for it at a launch point. So you’re kind of in a space that I can imagine right now; fairly heightened, there’s some anticipation. But I also think about how amazing it is that I’m in Turkey and I have a copy of your book. |

|

| 12:57 | I’m in Turkey, and I know we kind of take for granted that we can communicate so much online, but even a matter of years ago, there would have been difficulty in having this conversation. But here, you can call in St. Louis, I can call in from Izmit, Turkey and we can have this conversation wherein time sort of collapses, and we meet at this point and we can talk about creativity and writing.

And that’s something I never get tired of marveling over. I just think it’s such an amazing thing. So the fact that I have a hardcopy in my hands and I can still look at the cover while we talk is a really special think to me because it connects me to the book, it connects me to you, it connects me to my home which is in Wisconsin, where I was born and raised. |

|

| 13:58 | So I admit, I did take an interest in the book because of where it’s located; that’s one reason, as a place very close to my heart. But I just felt there are other things that we could relate to, like you’re a teacher, a mother and an author.

While I imagine there are major hurdles, I’m curious if there are any unexpected insights that you’ve gotten from combining these three really big things – being a teacher, mother, and an author all at the same time? Rebecca Rasmussen: Before I had my daughter Eva, I was still writing in graduate school in Massachusetts, and I had sort of a very unhurried life like… oh I could just work and I’d have a couple of things, French fries and coffee. And my husband might make me an omelet. And then sometimes, I’d even go back to sleep. |

|

| 15:13 | So all of that stuff sounds glorious to me right now – like a vacation. But, I think I was more particular about the way in which I got my writing done. I wasn’t picking the sounds like, “the room has to be this color and this light,” but I was like – I like to write in the morning. I like to write by the window. I like to write with this music playing. It was very particular. I like to write with my husband out of the house. And now since I’ve had [Eva], I’ve written in the car for a couple of hours at a time. I’ll write anywhere and if someone says you have an hour, go, that’s how I get it done. And as she’s gotten older, it’s a little bit easier because she’s in preschool a couple of days a week for the mornings, so I’m like, “oh wow, it’s three hours of unadulterated time.” Still it’s a blessing. | |

| 16:06 | Though I have fond memories of the late-waking days, I actually don’t have the same problem of internal pressure or blocking. I write the words faster and the emotion faster, than when I was doing it with the luxury of all the time in the world or that sort of thing.

Rose Deniz: [Laughter] I remember the times I had a whole day. I knew that we’d have that in common, I think and I can really empathize with the thought that since having children, I’m actually far more productive, which seems like it would be the opposite. But if you have an hour, you’ve got 15 minutes, you go. |

|

| 17:05 | That doesn’t means that I’m always productive with those 15 minutes, but I find creative ways to slip in time. Having a notebook with me at all times or even when the kids are in the bathtub – an idea comes to me then I go run and write it down.

I look at every opportunity as a chance to further my goals, but they might be in miniscule steps.

Rebecca Rasmussen: I love that, though. I can totally relate to the bathtub thing. I don’t even know if mine are particularly special, but they might be the next strands that leads me to the next strand of a story in there, and that’s wonderful. Rose Deniz: My next question is – how do you handle inspiration in opportune times when you’re in the car, or making dinner? |

|

| 18:05 | Do you think there’s some sort of advantage to having your hands occupied with some task cause your brain kind of absorbs and distills those ideas a little bit?

Rebecca Rasmussen: I think so. I also run a lot and during my run, I often come up with [ideas], and it’s interesting cause it’s not the first 15 or 20 minutes of run, it’s when I get to the point where I’m sort of tuned out. Obviously, some part of my brain is letting me move forward, but it’s just this very creative space where it does certain things – there might be a problem in a scene, and I’ll just know how to make it better and fix it, without having thought too much on the surface about it. It’s a deeper feeling that comes. And definitely during dinner, oh my gosh, when I’m cooking, it’s true. It must be something that I have when my hands… |

|

| 19:02 | Rose Deniz: There’s something about chopping vegetables, I think, the sound of the knife on the chopping board or something that connects with that quiet space inside.

I’m not a runner right now. I hate to say I’m a former runner because saying I’m a former runner will just make me sad; I still think of myself as a runner. After an injury several years ago, I really haven’t run much, but from 14 until about 26 [years old], I ran nearly every day or every other day. And so I can relate to what you’re saying, when you get to that place in your run, everything kind of just disappears and you can kind of jive into the groove of thought. It’s not that the ideas come at you, but you create a quiet space to appear. |

|

| 20:04 | I think there’s a big connection. There’s also [a connection] in terms of discipline with running and writing.

Rebecca Rasmussen: Absolutely and actually, I just read a blog before [we talked], a guest post of [a friend] about running. I always have a very hard time talking about running in my writing because I can’t quite find a way to describe that feeling of absolute joy that at certain parts of a run I will have, without just saying it’s absolute joy that you quite evoke with running. [Laughter] Rebecca Rasmussen: I really thought about that idea of discipline too, and even a lot of people I know when they were in high school ran cross-country and things like where you run off the course and then you come back. It’s their glue. |

|

| 21:06 | You know, for a lot of races and to master running with a pack, you’re on your own and it’s so interesting to me as an adult thinking about this 13-year old freshman girl Rebecca running through the woods for the first time and powering through and how at first, I didn’t.

I had to quit one of my first races in and I felt completely justified like, I hurt, I have to stop, I’m walking back. [My coach] lost it then, but in a good way, like, “Yes, I never wanna see you quit again and here is why.” It was one of the big lessons of my life. I think from then on out he was like, “You have to crawl in on your hands and knees if your legs are not broken. This is teaching your discipline, self-discipline. It’s not about how fast you run. You can walk it, I don’t care what you do, but don’t quit.” |

|

| 22:00 | So for me, that sort of lesson is completely valuable in my writing life, because I have a lot of friends who are really talented writers and who gave up because it got a little tough with publishing and things like that and didn’t power through. I kept wanting to grab them and say, “Keep going! Get on your hands with me, just crawl with me.” Because that’s how it is for both running and publishing.

Rose Deniz: There are two types of people in the world: runners and non-runners. Not that it can be that simplified, but I do think there’s something about a runner; they know when to up the ante and they know when to face the challenge and when to back off. Cause if you know your body well enough, you’ll know not to push it. I mean, if you’ve really done running for several years, you can feel it in your bones and your muscles. |

|

| 22:59 | Even when I was in graduate school and art school, I had a running buddy. I would try to get people to run with me and they would quit on me, because if you told me to come in at 5:30 in the morning, I would be up and I would be out the door [at 5:30] because that’s how runners think. Like, you got to go – you just go. And there’s some sort of pleasure in pushing yourself further than you thought you could go.

Rebecca Rasmussen: Absolutely. You’re making me want to go on a run! Rose Deniz: I know. It’s like 12:00 midnight here in Turkey and I want to go outside and run. But I think what I’m trying to get at is that discipline sets the stage for creativity. |

|

| 23:52 | [Creative] insights might come in the middle of the night. It could be anytime and you’re just supposed to sit there and let them come to you even at inconvenient times, but if you prepare yourself much like you would as a runner, and you expect that there’s going to be some discomfort, if you continue with it, you will get to that place where it’s really pleasurable.

If you know that, that you could push through it then yes, you will succeed. You will keep going. Rebecca Rasmussen: Yes, I think that [running/self-discipline] is a self-confidence-boosting activity, actually. I think that’s where, some people I know that are very talented, just have an inability to push just a little harder when you feel like you’re being beaten down a little bit. You just keep going. |

|

| 24:50 | Yes, maybe we all need my track coach Mr. Baker to come over and say, “don’t you dare stop,” you know?

Rose Deniz: You can’t say I’m tired, it hurts. I mean you can’t. If you’re a runner, that doesn’t cut it, because it’s right behind that wall of tiredness – which I think is really akin to mothering, too, so we can draw this comparison between running, writing, and motherhood, which is part of my original question even. And I think most of my frustrating moments have happened when I don’t realize that I’m at the wall and if I’d just hang tight a few minutes longer or an hour longer, it’ll be fine; I’ll get through it. That’s the hard part, maybe, about juggling all of those things at once. Do you feel like that happened to you too? |

|

| 26:00 | Rebecca Rasmussen: Now that Eva’s older, because I do have more luxury of time again, some of the old, “oh, I’ll just sleep and have French fries and coffee,” comes in. I think with mothering, it depends on the stage. Sometimes, Eva will go through a wonderful six-month period of not waking up [in the middle of the night], and sometimes she’ll wake up every night even though she’s almost four, with nightmares. So your levels of tiredness, hurt, pain, all of that gets pushed at different times, I think.

Being a mom, I think I’ve just learned to appreciate the moments where everything is peaceful and lovely, but also to push through and write when everything isn’t peaceful and lovely. It’s fruitful too, because for me it’s like, “OK, if I can’t make her nightmares go away, the only thing I can do right now is settle them.” I can create this whole place on paper that’s magical and interesting to me, totally aside from the situation I may be having at home and mothering or worrying about her or something. |

|

| 27:14 | It is really luxurious. I want to be in Wisconsin, I’m going there today in my writing, that kind of feeling.

Rose Deniz: When I think about when the house is quiet and they’re not there, it’s a very different experience than when the house is quiet because they’re sleeping. And I almost prefer the house is quiet because they’re sleeping at home rather than them being gone, because I don’t know how to deal with the starkness of the quiet. |

|

| 28:06 | Rebecca Rasmussen: It’s a stark transition. I mean even now, my husband took my daughter to go to the library to check out some books and I know they’re coming back in an hour, but it’s very quiet in here.

Suddenly, some of the things in our home that are my daughter’s little toys and stuffed animals that are the warmest, fondest things in our house feel very different when their beloved owner is not here. Even when she’s sleeping, knowing she’s in her room, it creates a sort of peacefulness in my real life so that I can go into my creative, imaginative one with peace. |

|

| 29:11 | Versus [when] things are upset in my real life, I have a much harder time. I want to work those things out first before I work on my writing, usually. That can be a startling too. I want to figure this out; I want to get to the bottom of this issue in real life, but yet I have to go right through, that kind of thing.

Rose Deniz: Well I think there’s something about when they’re out of the house, your mind travels with them too; It’s like, “OK, she’s at the library. What is she doing? I wonder what book she’s picking up?” You can never stop your mind from wondering and asking those questions. Whereas when she’s home, you know what she’s doing. I think that’s something as a topic that I talk about a lot on my blog about living a creative life; I’ve never believed that parenting and being an artist or a writer have to be separate. |

|

| 30:09 | It doesn’t mean that I think it’s always at the same speed or pace as people that do not have children. But I pretty much firmly put my foot down. I can be a mother, and an artist, and a writer at the same time.

And at the same time, those old rules about what you can and can’t do disappear for me the longer I keep exploring this question about living a creative life. That all of the things that we do [cultivates] that creative space. |

|

| 30:55 | I’m curious about how creativity fits into your daily life. [For example], you get that French roast coffee; that’s such a pleasurable moment. Nearly as important maybe, as sometimes more productive like crossing something off a list.

So, what are the moments that you find are creative in your day that [cultivate] creative space for you? Rebecca Rasmussen: I think that I love my schedule when I go on my teaching days, because I go to my favorite coffee shop and park in that neighborhood and get a cup of coffee. |

|

| 31:47 | Even when it’s cold, I bundle up and I walk about a mile to the school that I teach at, and that walk is in this gorgeous old St. Louis neighborhood with all these beautiful tall trees. In the summer, it’s very, very, very hot in St. Louis and it’s one of the few places that there are grand old shade trees on.

So for me, that walk and that cup of coffee while I’m walking is one of my favorite parts of the day, because there are also really big huge homes that I wouldn’t wanna live in but they’re so interesting… Rebecca Rasmussen: …and there are flowers and there are flowering trees. It’s really beautiful and I love that. The birds are really vocal on their streets and so it was really cool this fall, because when they were all flying away, there were these great, great, great flocks of birds in that neighborhood getting ready to go. So that was really beautiful in a literal musical sort of all. |

|

| 32:52 | But then also, when I’m a little bit stressed out or I’m having some issues with the story, I will say to myself, “I wish I didn’t have to go teach. I wish I didn’t have to go teach. I wish I could work this out.”

But I’m always so happy after my class is finished, because I feel like even though I’m not teaching creative writing right now – I’ve been teaching literature and composition, and so it won’t even be on the topic of writing, necessarily – I feel so much release of energy. They’ve given me very beautiful, lovely energy and I’ve hopefully given them some good energy. By the end of it, I feel there’s this wonderful exchange of energy and I always leave sort of bouncy and happy and smiley. I think that it tells me that I should be teaching and that I should always continue to do that. I think that that energizes me so much, especially when I’m frustrated with my own work, so I find that to be a really inspirational moment of my day. Though, I can’t quite pinpoint exactly why. It’s just that to see them all raising their hands and getting involved and interested, it just is wondrous for my own inspiration. |

|

| 34:09 | So, I have to thank my students all the time, because they really do so much more for me than they understand or that I could even explain in words to them. So those are huge parts of my day that I find wonderful.

I usually do most of my writing outside of my house. I go to crazy, nondescript coffee shops to work, and sometimes after I teach if I don’t have to pick Eva up, I’ll go to the Starbucks on the corner and I love that it’s anonymous, yet I know everybody that works there and they’re certainly not anonymous. So just little things, even the man at the gas station can inspire me with his kindness. It’s not much, it doesn’t take much for me. I used to think of inspiration as like, “I must look at a piece of art in order to be inspired,” or something but you know I think now, I just try to appreciate the little moments of my day and not think about it that way. What about you? |

|

| 35:19 | Rose Deniz: I’ll admit that I haven’t been to a museum in a really long time. One of the very same reasons that you just said that you find inspiration in unusual places, because you’re training your eyes, you’re training your voice, you’re training yourself to tune into details and those things don’t necessarily happen in a museum.

Much of my practice is not physical anymore, tangible. Much of what I do is online and illustrating for the web is a really different experience than having a painting on the wall. I love paintings on a wall, but I also love unusual details in real life. Things that can’t get pinned down like tangible objects, a painting, canvas. |

|

| 36:18 | Living in Turkey, there is so much stimulation around me that even after six years of living here, I’m still overwhelmed the minute I step out my door. I feel like I take things in a different way than I did when I was in the US.

Or maybe, I even felt under-stimulated [in the US], and so I would go to a museum, I would go to concert in order to feed that part. While here, I feel like I continually need to back off. I need to go back to my quieter space and take all the stuff that I’d accumulated outside and bring it back. Or even leave it at the door because it’s almost too much. |

|

| 37:06 | That was part of, I think, learning a second language. It’s also that Turkey’s sometimes chaotic, sometimes noisy; it’s a completely different experience than a nice rural Wisconsin upbringing.

My summers were filled with laying a blanket on the grass and reading; that’s what I did all of summer. And the winter, I sat in our living room in a rocking chair and I read; that’s it. I mean I just think about that uninterrupted time where it’s just the sky above me, and the blanket below me when I’m reading. That’s something I know I really sort of pine for now, but I have to know that I’m in a different space and so I don’t want to necessarily replicate that. I don’t know if I could actually go back to living that way, to be honest. |

|

| 38:11 | Rebecca Rasmussen: That’s interesting that you feel that you’ve had such a shift from living between two places and probably growing up and older and with children but yes, I can absolutely see that.

I think there is a big part of me that would want to get back to the girl on the blanket too, in some ways. Maybe it’s getting back to that girl, sort of metaphorically, rather than literally – like you must go back to Wisconsin and sit on a blanket. |

|

| 38:57 | Rose Deniz: Yes.

I know that even though I’m still living abroad and I miss my home and I miss my roots, it still doesn’t necessarily mean that moving back would be the best scenario. I just think that it’s interesting what our memories tend to pick out as being important. For me, that’s why I really am drawn to your book because it’s so much about a physical location. I grew up with rivers and creeks around me and tall trees, and so the sense of the earth seems so solid beneath my feet. All that time with that space to just think and dream. That’s, I think, something really special, honestly, about that corner of the world [Wisconsin]. You really tap into that [feeling in The Bird Sisters] in a really remarkable way. I know that I have seen the places that you’ve written about, but yes that’s still its own world. It has that Wisconsin tinge, so for me it’s so appealing. |

|

| 40:31 | Rebecca Rasmussen: For me the book couldn’t have ever happened without Wisconsin. There’s just this so irrevocably tied to Wisconsin; this is not something that could take place in even Illinois, or Iowa, or Michigan. It’s so tied into what you were talking about, the tapping into those memories and what the land means to me, trying to figure out through those memories my attachment to that place but yes, absolutely, what essentially always comes first with the book, is the place. | |